Subject to the above, the AE and SA will release the ITO/BPO SOW under the GMSA ASAP (COB latest) following SOAR and FPA approvals, including for TSS/ES ICOEM GTM which may require RLT.

It would not be an exaggeration to say many emails I receive include sentences very similar to the one above.

Sometimes these emails start out innocently enough – a defined term here, an acronym there. But by the time you get to the final paragraph it feels like someone is just shouting random grouped letters at you.

Other times, it’s abbreviation city from the opening sentence and unrelenting until the final “BR” sign-off (which in many cases is followed by the author’s initials only).

In many organisations, the acronyms have almost taken over. IT and engineering companies are usually the worst offenders, but it seems almost inevitable that as any business grows, regardless of the industry, the use of acronyms becomes increasingly BAU. And what starts as a well-intentioned exercise to simplify communication between employees and teams ultimately causes greater confusion within the organisation, and makes for a very daunting first few weeks (or months) for new starters as they come to grips with your company’s capitalised codes.

In his aerospace company SpaceX, Elon Musk (who also founded PayPal, Tesla and SolarCity) identified acronyms as a serious concern and took extreme action – he decreed acronyms used by employees required his personal approval, and banned the use of all others. While this may sound OTT, I’m sure many of us have wished for something similar when churning through email after email of TATs, SLAs and IoTs (I know I certainly have).

Acronyms aren’t all bad, though. In fact, when used correctly and selectively they can be extremely effective at keeping communication short, sharp and to the point (when’s the last time someone told you they were getting a Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus diving lesson?). However, in a business context, the use of acronyms is effective only up to a point, after which they rapidly become and remain ineffective.

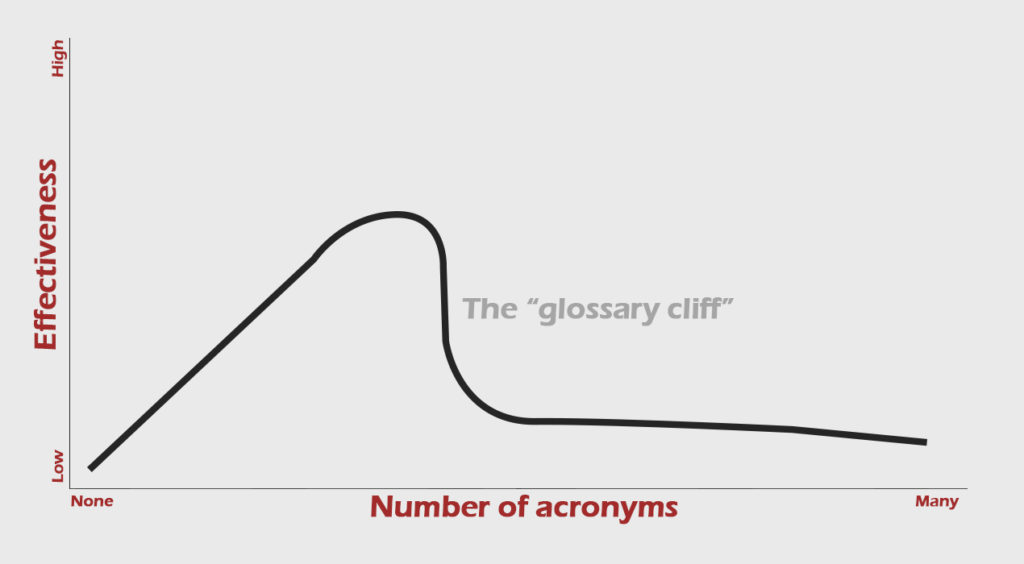

The below graph (which I call the Acronym Effectiveness Curve) attempts to illustrate this theory:

As the curve demonstrates, in the beginning life is grand – the more acronyms being used, the more effectively they simplify and clarify our communications (with “effectiveness” meaning either the ability of the acronym to be understood or the overall effectiveness of the message incorporating the acronym – I think the same basic rules and relationships apply to both).

However, the organisation soon reaches a saturation point for acronyms. While this point may be at different positions for different companies depending their on size, industry and workforce demographics (among others), I believe there is a common underlying reason for this “tipping point” – it represents the maximum number of acronyms that a workforce can recall and apply from memory.

The curve also assumes that as soon as people need to lookup the meaning of an acronym in a wiki or glossary, the effectiveness of the acronym as a communication simplification tool is lost. It’s also likely that, faced with an unknown acronym, a reader will merely press on and either ignore or assign their own meaning to the acronym, which further accelerates the downswing in the above curve, creating what I call the “glossary cliff“. Once an organisation tumbles over the glossary cliff, the effectiveness of its acronyms stagnates and slowly declines over the long term as the number of acronyms grows.

Companies need to be mindful of the glossary cliff and ensure employees have sufficient guidance for creating and distributing internal (and external) communications. While specific strategies to achieve this are outside the scope of this post, managing the glossary cliff will help ensure your company’s communications style remains a fantastic asset which can embody and help promote your organisation’s culture, and also improve the productivity of your workforce.